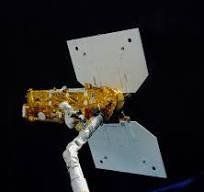

Oct. 5, 1984: The Earth Radiation Budge Satellite on the end of the Shuttle’s robot arm.

*****

He scoffs at the notion that the number matters. Yet our mission commander, Robert “Crip” Crippen, facing his fourth flight, cannot avoid the number 13. He’s just back from STS- 41C in April 1984. That flight was once called STS-13 before the flight order was scrambled. To avoid — or perhaps increase — confusion, NASA came up with a new way to designate flights. It combined the fiscal year of launch, meshed to a “1” for a Kennedy launch, along with a letter designation of the payload.

We’re Crippen’s new crew of Jon McBride, pilot; Sally Ride, Mission Specialist #1 (and flight engineer); Kathy Sullivan, Mission Specialist #2; Dave Leestma, Mission Specialist #3, Canadian astronaut, Marc Garneau, Payload Specialist #1 and Paul Scully-Powers, Payload Specialist #2. Our flight is designated STS-41G But as fate has it, we will be the 13th Shuttle flight. There’s that unescapable number again. And here’s another number for you, a luckier one — seven. We seven are the largest crew to fly the Shuttle to date. We will take Challenger on an Earth observation mission spanning 8 days 5 hrs. in October.

We’ve been training a year, but for the first six months, we were a crew of six, as Crip, assigned to two missions at once, was busy with STS-41C. NASA, envisioning a rapid build in the flight rate, wanted to see how quickly a crew member could cycle between flights. Crip said he’d give it a test — only if he had an experienced astronaut, someone he’d flown with, to take charge of training of the second crew until he returned from his preceding flight. The person he wanted? Sally Ride.

Sally flew with Crippen on STS-7 in 1983, the flight that made her the first American woman in space. Knowing what he’d expect from the crew in training, she served as Crip’s stand-in overseeing training activity. You could consider her the first woman to command a Shuttle crew, at least temporarily.

We will fly our Earth observation mission from high inclination orbit tilted 57 degrees to the equator. We will range much farther north and south that the Shuttle’s normal 28.5-degree inclination. The path will take us over 63 percent of the Earth’s surface and 90 percent of the planet’s population. As our first task, on day one, we will deploy, the Earth Radiation Budget Satellite (ERBS). The rectangular satellite sporting two solar panels, weighs 4.960 lbs. We’ll deploy it with the robot arm, and it will stay in a low orbit of 378 mi. altitude. It carries a suite of instruments to measure the incoming solar energy and that radiating back into space by the Earth — that’s called the Earth’s radiation budget, the balance of incoming and outgoing heat. In effect the satellite will measure the Earth’s temperature and any changes over the lifetime of satellite. It also carries instruments to measure the concentration of aerosols, nitrogen dioxide, carbon dioxide and suspended dust in the atmosphere. Sally Ride will operate the Remote Manipulator System (RMS) robot arm for the deployment.

Kathy Sullivan is in charge of a second major payload that will be operated from the payload bay, the Office of Space Terrestrial Applications (OSTA-3) array of instruments housed on a U-shaped pallet in the payload bay. Prime among them, the Shuttle Imaging Radar (SIR)-B. SIR, using a flat rectangular antenna that unfolds from a sandwich of three panels, will produce images of the surface and subsurface using microwave radar pulses, revealing different types of terrain. The OSTA pallet also holds sensors that will measure atmospheric pollution and the Large Format Camera that will take stereo photographs of the ground.

A major event will take place toward the end of the mission — a spacewalk. Kathy Sullivan will become the first woman to walk in space. Well, she would have been until Russia, as usual, robbed her of that bit of history — and at the same time stole the title of first woman to fly twice in space from Sally Ride. In July, cosmonaut Svetlana Savitaskaya flew for the second time, part of a short mission to the Salyut 7 space station, and made a spacewalk, testing welding techniques.

On their walk, Kathy and Dave Leestma will test satellite refueling techniques. They will pump highly toxic hydrazine between two tanks, simulating the refueling of the Landsat 4 satellite. The work involves piercing a mock fuel system and connecting a refueling line. Hydrazine will be pumped through a valve module. Although Kathy, a member of the 1978 astronaut class, outranks Dave, who came aboard with the class of 1980, he will take the lead on the EVA because she has responsibility for the OSTA experiments. That’s what our mission commander decided.

Six months before flight, Crip is free to take over the training reins. Everything clicks perfectly toward a launch at 7:03 a.m. EDT on October 5, 1984, in what may be the smoothest countdown in Shuttle history. We’re a fun crew to be on. Take Kathy Sullivan and Sally Ride, standing in the white room at the hatch, waiting to board the Shuttle, cameras trained on them, knowing the press is watching. They pull a little gag that they’re sure the press will lap up. Like World War II pilots before a mission, they pretend to synchronize their watches!

It’s just before dawn, the skies reddish with dawn to the southeast when our engines ignite, sending a pulse of light that finishes off the last traces of night. And we punch through a bank of clouds, racing into sunrise. And 8.5 min. later, we arrive on orbit. Have we broken the bad luck of the number 13?

We quickly set up for orbital operations and move into deployment mode just three hours after launch, running through a long list of steps, toward deploy of the ERBS at 8 hrs. 25 min. after launch. Sally Ride and Dave Leestma, the backup arm operator, take center stage. Ride lets Leestma unlimber the arm, check it out and move it in to grapple the satellite. She takes over, lifting ERBS and holds it steady for deployment of the two solar panels. We send the command to open the first first panel. There she goes — perfect. We command the second panel open and . . .

Nothing happens. Houston says, try the back up command. We send it and . . .

Nothing happens.

Houston suggests pointing the satellite into the sun — maybe that will unfreeze the mechanism. That doesn’t appear to do anything, at least at first, as we pass over Australia. We’re about to go out of communications range for 20 min.

What do we do now?

Sally exchanges a look with Dave. A mischievous look. She’s never one to be bound by rules.

Are you thinking what I’m thinking?

She asks Crip, “Do you mind if we try to shake this thing loose?”

“Go for it. Just don’t break it.”

She moves the arm to the left as fast it’ll go, which isn’t very fast, then back to the right. It gives the satellite a jolt. Nothing happens . . .

She tries a second time.

Something’s happening! Slowly, in jerky motions, the wing unfolds.

We come back into communications range over the U.S. Houston calls, “OK, we’re with you.”

All we say, like guilty children is: “Well, take a look at the satellite. See if we’re ready to go.”

It is, and they asked what we did. “We’re not going to tell you.”

This was fun. It’s rare you get to do something unscripted during a flight, take your own initiative without Houston looking over your shoulder.

Next, Kathy Sullivan takes the spotlight, activating the SIR-B radar. The two leafs of the antenna must be swung open. When the first one pops free, the whole thing wobbles and shutters. That gives us a moment. But when the second panel opens, it steadies the rig. Rock solid. Everything checks out — ready to gather radar images that will be “dumped” to the ground through the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite in high geostationary orbit. The high-speed data must be transmitted through our Ku-band dish antenna, which we’ve swung up at the front of the payload bay. It must swivel to keep track of the relay satellite . . .

At the end of this long day, tt begins wobbling wildly. The drive mechanism has failed. Obviously rendering it inoperable. If it can’t be fixed, the SIR-B data will be lost. And that threatens to shorten our flight.

Suddenly the number 13 is living up to its reputation.