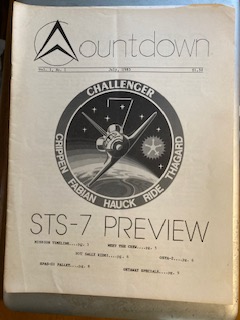

The cover of the first issue of Countdown, July 1983

*****

Part 2: Live from the press site

I was going to see a Shuttle launch, STS-7 on June 18, 1983. I’d planned to see the maiden flight of Challenger in January 1983, but a series of delays postponed the flight until April, a sign that the program was still undergoing birth pains, and my plans were canceled. I’d have to settle for the second launch of the new Shuttle, the first covered by our new magazine, Countdown.

In late April, I took a grand road trip to three NASA centers, Johnson, Marshall and Goddard, as well as NASA Headquarters, introducing the magazine, giving it a face. First stop, the Johnson Space Center where I talked to one of the “voices of Mission Control,” Terry White. He asked me as many questions as I asked, I said in my journal, including who our audience was. “Space buffs and interested lay people,” I replied.

“‘Space cadets,’ he said, looking me straight in the eye and looked for a reaction. I smiled weakly & said, ‘Yeah, you could say that’ — mumbled it.” Now, more than 40 years later, I wish I’d said — the public, the people who pay your salary.

Outside the building, I saw something very symbolic. “They have a Saturn V on display — #14 by the markings.” It was sitting there exposed to the elements. “It’s a sad sight — paint blistered and bleached, insulation peeling, patches stripped away . . . in slow decay.”

Although all three stages were flight certified, they came from different flights. The first stage indeed was from the 14th Saturn V, which would have launched Apollo 19. The second stage was from the 15th and final Saturn V, and was used as a backup for Skylab. The third stage came from the 13th Saturn V, with the first two stages used to loft Skylab. In 2004-2006, the stages were refurbished and moved into a hangar in what is now the George W.S. Abbey Rocket Park at JSC.

*

The press center at the Kennedy Space Center was crowded and I was one of them, back barely a month since my big tour of NASA facilities. Sally Ride, set to become the first American woman in space, was the focus of attention, drawing quite a crowd for the launch of STS-7. I remember a stream of headlights on the roads as I drove to the space center in the early morning.

It was June 18, 1983. “5:35 a.m. — here we are — in the press center — watching the astronauts enter the Shuttle over TV. So all is well. This is neat! I guess that’s all I can say!”

“7:55 a.m. — back in the press building — Challenger is in orbit! I’ve just come in from watching it. My reaction: humm. I guess that’s it. I wasn’t overwhelmed as I expected to be from the build-up. Perhaps my expectations were too high. The view was excellent from where I was, the steam & smoke did not obscure the view. The view was as good as on TV — and it seemed to move slower than on TV. But the noise was much less than I expected — I could feel it like loud music, but I’ve been to fireworks shows that were louder and more startling.

“In a way, maybe I was too busy taking photos — I think I got better ones than I expected. I was surprised by how long after launch you still could see the Shuttle.

“So overall it was excellent — I guess I just had too much expectation that the earth would tremble like an earthquake & the air would quiver like a violent storm — which did not happen.”

There’s much to that — imagination is more powerful that reality. Also, a Shuttle launch happened so fast, I didn’t have time to absorb it all by watching just one launch.

Also, I didn’t fully appreciate the dangers. The chance of a launch failure was appeared remote to me. I didn’t believe anything catastrophic could happen. The four test flights of 1981-82 had proven the system “operational,” as NASA said, hadn’t they?

*

My reaction to the next launch was anything but muted. STS-8 was set to make the first night launch on August 29. I didn’t have time to write in my journal until the early next morning.

“At KSC . . . STS-8 is a flyin’. What a liftoff — like a dawn. That’s what got me — it wasn’t just a small intense light. It seemed diffuse — everything lit up with about the hue and intensity of early sunrise. It even seemed to make more noise than STS-7 — really popped at you a few times.

“And then the false dawn faded — into a second moon to a fuzzy one half-hidden behind clouds.” I remember that the light seemed to bounce and rebound in those clouds. Like a scene from Close Encounters.

*

I traveled to KSC for the maiden launch of Discovery in June 1984. As office work took up more of my time, I would not have time to attend launches after this one. The first attempt, on June 25, was scrubbed when the backup flight computer failed. The launch was quickly turned around, set for the next day.

“7:04 [a.m.] — back at the Cape for another launch attempt– supposedly 1 1/2 hr. from now, but there’s heavy ground fog. They’re ‘optimistic’ that it’ll burn off. Ha — you can’t see the Shuttle!”

“1:57 p.m. — guess what — it did not go off (again!). This time they got to T minus 4 seconds — the engines ignited — and stopped! They’d gotten an indication of a bad fuel-pump valve, so it automatically shut down.

“And of course we didn’t know that at the time. We heard the low rumble of engine start — and then a screech like railroad cars being braked hard.” Growing up near railroad tracks, I knew the sound of box cars banging to a stop.

“‘Abort!’

“And that was it — the Shuttle just sat there.”

Later, I added detail of the day. “Up at 5 and [drove] in there [the press site]. The fog burned off just in time for a good ‘go’ for launch. And it ticked down to 4 sec. when all came to a stop.

“It’s strange — a little excitement cuts through my usual reserve.

“One reporter — one I vaguely knew — had a good recording of the launch. We stood around replaying, trying to figure what was said, what was going on. All except the L.A. Times reporter who scoffed, ‘why are you doing that? They’ll tell us at the briefing what happened.'”

Or maybe not.

As controllers read off pressures and systems status in a flow of technical language, a fire detector at the base of the Orbiter went off. Hydrogen expelled the from engines had ignited. Fire suppression water “rain birds” make two attempts to extinguish the clear hydrogen flames. Each time, the fire starts again.

Finally the third attempt does the trick. I did not fully appreciate the danger of the situation. Only when astronaut memoirs and biographies were written years later, I learned how close we’d come to disaster. The clear flames of hydrogen might have extended as high as the crew access level. The crew damn near opened the hatch to make a quick exit. If they had exited the Shuttle, they all could have been killed.

*

I kept waiting for the Shuttle to overcome the failures and delays, to prove it could meet the launch schedule, to become the efficient and reliable launch system that could open up the space frontier. I kept waiting for the Shuttle to recapture the spirit of Apollo. I was still waiting on a cold January day in 1986, as NASA conducted what seemed to me a publicity stunt.