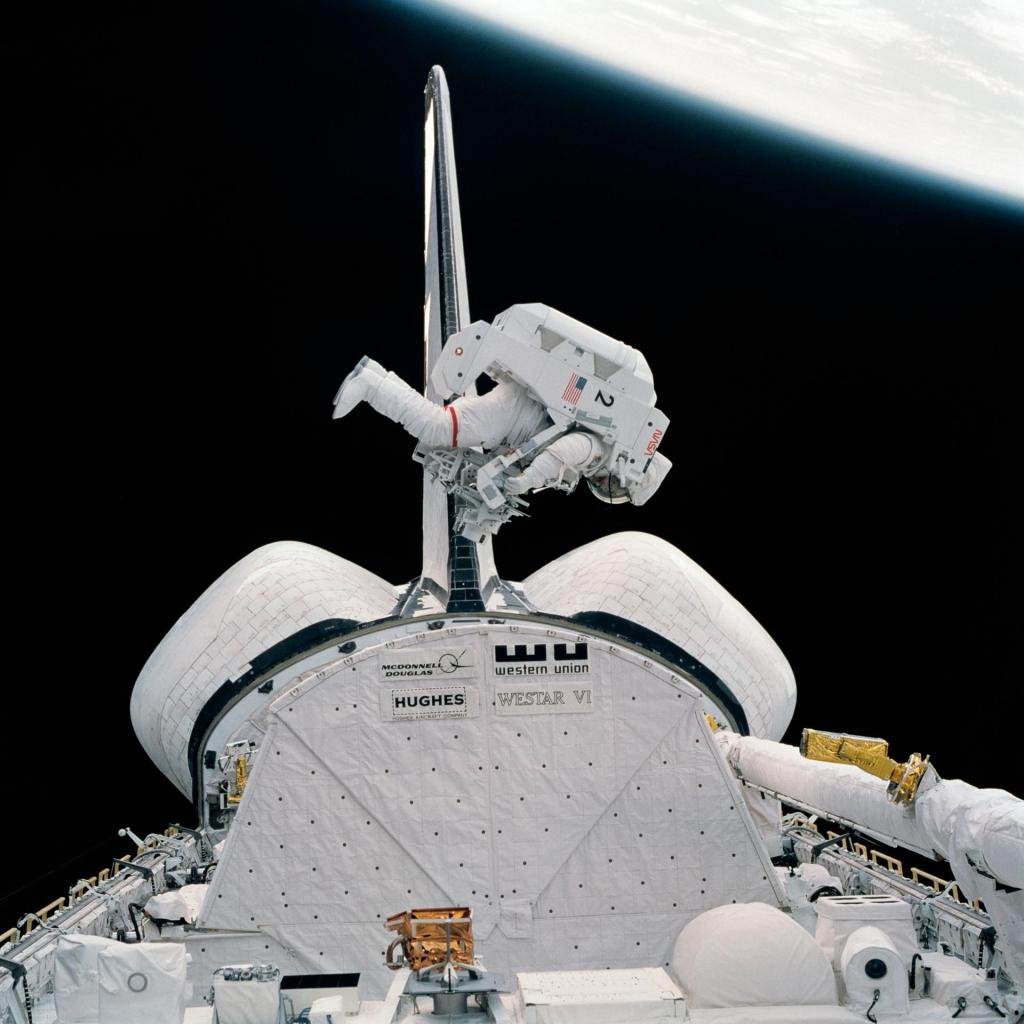

February 9, 1984: Bruce McCandless in the MMU descends toward a docking using the Trunnion Pin Attachment Device ((T-PAD) locked at the front of his suit.

*****

STS-11 EVA #2

It’s February 9, 1984, the seventh flight day of our STS-11 (41B) mission aboard Challenger and time to get back to (outside) work, our second EVA. The goal of this spacewalk: Conduct a dress rehearsal for the repair of the Solar Max satellite on the next flight. The RMS robot arm will lift the Shuttle Pallet Satellite (SPAS) and set it turning like a revolving advertising sign. The disabled Solar Max satellite will be spinning just like that when the crew in April approaches it. Our spacewalkers, Bruce McCandless and Bob Stewart, each in turn wearing the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) will approach the SPAS, match its rotation and dock with it. To grab the SPAS, they will be equipped with the barrel-shaped T-PAD that clamps its teeth on a trunnion pin, as will be on the Solar Max.

Preparations for a spacewalk take hours. We’ve got Bruce and Bob in the airlock, ready to swim into the payload bay. Our pilot, “Hoot” Gibson,” is activating the robot arm. Oh, no — he receives a fault message that the “wrist” joint is failing. He tells Houston, “When I was maneuvering the arm up to overhead the SPAS, it wasn’t responding exactly the way I thought it out to. . . And looking out the window, it may be that . . . the wrist yaw I don’t think was following what we were asking for.”

We run through a series of malfunction procedures. Our commander, Vance Brand, says to Houston, “If you think we’d like to get everybody going out the hatch about the same time independent of the RMS problem, why, we’ll proceed on with that.”

“Roger Vance, we’re go for for EVA.”

Hoot switches to backup mode of control. The joint works fine. But if this mode failed, now they’re be no backup. The arm could get hung up. Capcom Jerry Ross calls, “We are electing not to do any further checkout of the arm. We’d like you to cradle it, please.”

“OK, and Jerry, we’ll cradle the arm. That’s what we were expecting to hear, I’m afraid.”

The spacewalk goes on! Houston says, “We would like to conduct the nominal EVA timeline.” That is, though, with docking the T-PAD with the SPAS while its latched in the payload bay.

Bruce is first out the hatch, saying, “And it looks like another sunny day up here.” Bob follows, and Bruce swims for one of the MMUs we’re carrying and prepares it for flight. The pace of this spacewalk is more relaxed than the first one, affording the spacewalkers more time to look around. As we come up over the coast of Africa, Bob who is unloading tools, says, “This is nice not to be running so hard today. You can see the world.”

Bruce readies his MMU and T-PAD docking device which looks akin to an old-fashioned press camera and attaches to the chest of his spacesuit. Soon he rises from the dark depths of the bay, drifts along it as smoothly as a kite in a summer breeze.

We’re on the nightside of orbit. Bruce calls, “Hey, I can see cities passing out there. . . It looks as if the cities are very, very close constellations.”

We tell him, “We should be coming up on Houston pretty soon.”

“Bob, when you go over, why don’t you shine your flashlight at them.” Then Bruce exclaims, “That is really pretty; that is really neat!”

Bruce descends face down toward the trunnion pin on the SPAS. He appears curled around the T-PAD and steers it down over the pin. “OK, I believe I’ve completing a hard docking here. I’m going to try to pull myself off with MMU.” He fires the backpack’s jets to test how secure the lock it. The T-PAD’s grip remains solid.

He rocks a bit — the link holds steady. “There’s essentially no motion between the T-PAD itself and the SPAS trunnion pin.”

He releases and drifts off like a fish swimming to the back of the payload bay, then descends to its bottom. He approaches the pin again, with his head toward the bottom of the payload bay. “There’s a dock,” he calls. “The view isn’t quite as exciting from this position, but it works.”

Bruce parks his MMU in it’s support station. We tell Bob that when Bruce finishes, it’s his turn to fly.

“Well, I hope so. He promised me I could fly.”

“Did you get that in blood?”

Bruce’s permission doesn’t matter, he jokes, “I’ve got one [MMU] down here myself all gassed and ready to

It’s tag-team flying, and now it’s Bob turn to make some practice dockings, using the other MMU. He calls, “OK, there’s a good soft dock.” and then backs off.

“I’ll try to command a little upper angle this time to see whether we bounce off or not.” He flies in at an angle and still the T-PAD grabs hold of the pin. “I did a docking that time [with] what I would estimate to be about a 15 degree, or 10 degree at least, off-set and it did fine.”

He makes more runs at the docking pin, and Vance comments, “You look like you feel right at home in that thing.”

“I do, Vance. It’s really easy to fly. It’s really a nice little machine. I just wish it had a little bit more gas on it.”

As Bob stows the MMU, Bruce is working at the tool box. Suddenly, he calls, “Shoot! There it goes.” A portable foot restraint, looking like a breakfast tray, has come loose, is floating out the payload bay.

“Houston, Challenger. We lost our foot restraint. It’s starting to float out. We can get it if you wish — with the Orbiter.”

Our spacewalkers call, “Yeah, why don’t you.”

Houston calls, “OK, your call.”

Our spacewalkers say, “I’d let the Orbiter go get it.”

Our commander, Vance Brand, says, “I’m going to go get it.”

A set of foot restraints floats free from Challenger’s payload bay!

“He’s going to do a rescue scenario.” We’ve practiced retrieving an astronaut who has come untethered or suffered an MMU failure. This will be a good test of our skills. He gently thrusts the Shuttle upwards, slithering the payload bay to encompass the foot restraint. Bruce scrambles along the slide wire strung along the side of the payload bay. He raises an arm and catches the suspended foot restraint as easily as catching a softball.

Applause, please! We joke, “Well, ‘we deliver’ may have been the STS-5 crew motto, but we pick up also!”

And it’s back to work.

Bob conducts a test of refueling in orbit, as might be done with a Landsat satellite. He works at a mockup of the Landsat fuel system mounted in a Shuttle tool box. He connects a “fuel” tank containing freon rather than toxic hydrazine to an empty tank and pumps the liquid between the two.

“The hydrazine transfer stuff is going very smooth up until [now]. At this time, I cannot get he quick disconnect seated. I’ve gotten out of the foot restraints, put as much force on it as I can. . .”

After more work on the lines, Bob reports, “I just have to twist the freon valve open, but the quick disconnect on the other end of the line will not stay seated.”

The capcom says, “We’re looking at it on the ground.” They come back and say the line pressure will hold the quick disconnect in place, and he’s go to open the valve.

At the same time, Bruce is readies his MMU for another flight, and begins a series of engineering evaluations. He flies a set precise maneuvers to see how well it can hold attitude and make tiny position changes.

But in the middle of all this activity, something special is about to happen, something carefully scripted. We train TV cameras for the best shots of the payload bay.

“Bob, an you break off the hydrazine activity temporarily.”

“Yes.”

“. . . Why don’t we take a 5 min. break here, and then finish up these tasks.”

The duo takes positions we’ve worked out for the best TV. Bruce flies to the center of the payload bay and leans back as in in a reclining chair. Bob, pulling himself along one of the payload bay slide wires bobs into view, his legs floating outside the side of the bay. They make a pretty picture.

The capcom calls, “Challenger, Houston, the President of the United States.”

President Reagan speaks: “Commander Brand, I’d like to say a good morning to you and your crew. I’m talking to you from California. I don’t know exactly where you are; I know you’re up there some place. . .”

We sure are. After a hearty round of congratulations and well wishes, we get back to work. Bruce finishes his MMU evaluations, and Bob completes the refueling operations.

And with that, the two put their tools away tidy up the payload bay, making sure nothing is loose. “What else do we got to do to close out this place?” they ask each other.

“Well, I looked in both bays, and I couldn’t see anything loose.”

When everything is double checked, they move inside the airlock. “Outer hatch closed and locked.” The spacewalk ends after 6 hrs. 17 min. Now all that’s left of our flight is to pack up tomorrow and the day after, make one last bit of history: The first Shuttle landing at the Kennedy Space Center.