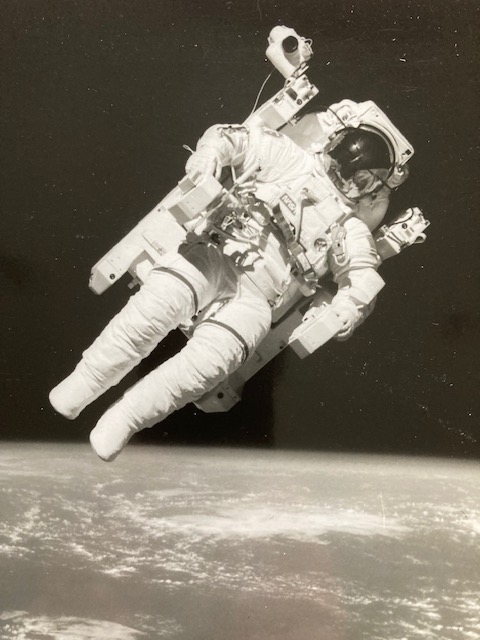

February 7, 1984: Bruce McCandless flies the first test of the Manned Maneuvering Unit.

*****

It’s February 7, 1984, the fifth flight day of our STS-11 (41B) flight, and time for Bruce McCandless and Bob Stewart to take center stage, along with the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) built by Martin Marietta. The unit measures nearly 50 in. tall with a width of 32.5 in. It fits around the “PLSS,” the portable life support system, the backpack that contains oxygen, power and coolant. Two MMUs costing $10 million each are aboard, stowed in the payload bay, one for each spacewalk the pair will make. Each is studded with 24 small thrusters that squirt cold nitrogen for thrust, each thruster delivering 1.7 lb. of thrust. The backpack holds 26 lbs. of nitrogen gas propellant and fully fueled weights 338 lb. (on Earth).

It’ll a full day’s work for us, outside and inside the cabin. We begin Extravehicular Activity (EVA) preparations about 3 hrs. before the walk is to begin.

Bruce and Bob are suited now, ready to exit into the long payload bay. The spacewalk is expected to last about 5 hrs. Let’s watch from the aft flight deck. From the cylindrical airlock at the back of the middeck, our spacewalkers report, “OK, here comes the outer hatch open. . .”

We say, “OK, we’re looking for you.”

“. . . Looks nice out there.”

Bruce and Bob, secured by safety lines, float out into the payload bay as if at the bottom of a swimming pool and immediately begin unstowing equipment. Bruce, who will be first to fly the jet backpack, goes to where it hangs on the wall of the payload bay in a support structure and readies it. “The MMU’s condition is generally looking good,” he reports. Soon he backs into it, locks into place, runs through the controls. And releases, and that includes from his safety line. He’s free flying and moves into the middle of the bay and stops, rock solid, facing us in the crew cabin.

He calls, harkening back to Neil Armstrong’s first words on the moon, “That may have been a small one for Neil, but it’s a heck of a big leap for me!” He moves up to the flight deck windows fluidly under the backpack’s control. We observe, “You look real stable out there.”

He rocks back and forth, forward and back testing the tiny jets and stability of backpack. He looks like a swimmer bobbing at the surface of a pool. We tell Houston, “He’ right outside our window here. Looks great.”

And Bob Stewart, working at a tool box, looks like a diver at the bottom of the pool. What a contrast between the rock-solid control the MMU provides Bruce and the awkward movements of Bob swinging this way and that with wasted motion.

Bruce seems to relax as he become familiar with the system, swinging his arms more. It’s time to make the first test runs back along the payload bay. “I’m going to head out over the bay, with your permission.”

He turns and drifts along, lazily rises up and over the bridge-like Shuttle Pallet Satellite (SPAS) spanning the mid-bay. “When you put in for a long translation, the thing shutters and rattles and shakes,” he discovers.

The big moment comes. “I’m going to leave the payload bay now,” he calls and then sheepishly adds, “with your permission.” He rises straight up as if on a stage-trick wire, but no wires here! When 15 ft. above the payload bay, he tilts so that he faces the Shuttle at all times. And backs away. “I could go faster, but why rush it?”

To us, eyes out the overhead windows, he appears to shrink to the size of a toy astronaut. “This is neat!” he calls.

When testing the various control modes, he reports some unexpected “chattering” when the thrusters fire in one mode, “attitude hold,” yet it’s no problem. These are the things he’s out there to find out.

He reaches 150 ft. “OK, and I’ll come back in. MMU . . . it’s real solid on stability.” And he comes back like a fish on a line.

The radar is unable to get a good lock on him, and he jokes, “Maybe I should have eaten some of those cans for breakfast instead of just the food.”

“Yes, your not reflective enough.”

He reaches the payload bay, flies right to our windows. “Are you going to want the windows washed or anything while I’m up here? ” he jokes. The round trip has taken 12 min.

Meanwhile, Bob is encountering difficulty with footholds in front of the tool box and stowing tools from it on on the Manipulator Foot Restraint (MFR) that will be attached to the end of the robot arm to create a work platform. He’s running behind schedule.

Immediately upon returning, Bruce sets out again for 300 ft. This time he shrinks until he’s just a tiny moon riding above the blue curve of the Earth. He calls, “I have a real good look at the Main Engines now.”

We peg him at 204 ft. He has a grand view of Challenger. “And to think this thing was sitting on the launch pad just a few days ago.”

“Yes, it’s a marvelous machine,” we add.

” . . . It’s really a beautiful panorama.” And he’s still moving out.

“We have you at 318 [ft.] and still opening a little bit.”

“Well, I ought to be closing now.

“Three-twenty and still opening a little bit.”

“How about three-tenths [ft. per sec.] closing?”

“Standby one . . . OK, 308 and closing at somewhere around .3 to .5.”

We warn him, “You have about 20 min. till dark.”

He says, “It looks real good out here from a sun angle and everything. Is this Africa I’m coming over?”

“Sure it.”

“Boy, it’s beautiful down there.”

He returns before we go into orbital night. His next task is to test the T-PAD docking device that will be used by a spacewalker to latch onto the Solar Max satellite. The device, with a protruding cylinder, attaches to the front of a spacesuit. Bruce tests it out, making a half dozen dockings with a trunnion pin on a support structure in the bay. He later reports, “That T-PAD works great.”

Alas, Bob’s trouble setting the up Manipulator Foot Restraint could cost him the chance to be the first person to take a ride at the end the RMS arm. Houston tells us “to make sure we keep Bob on schedule for his MMU task.” His priority is to test fly the MMU so that it is evaluated by two people.

We’ve got a circus of activity going on. Ron moves the arm into position for installation of the Manipulator Foot Restraint (MFR). McCandless locks the backpack in the support structure, and recharges it with the nitrogen that fuels its 24 thrusters.

Alas, we’ve run out of time for Bob to become the first person to ride on the end of the robot arm. Houston calls, “We recommend that he terminate once he gets the MFR installed, configured, and press on for the MMU.”

So after attaching the foot restraint to the end of the 50-ft.-long robot arm, Bob turns his focus to preparing MMU. Bruce tells him, “Enjoy it. Have a ball.”

The Manipulator Foot Restraint

Meanwhile, Bruce now will gain the first ride on the robot arm, locking his feet in the MFR’s foot restraints. Ron McNair with us on the flight deck controls the arm. Bruce is ready to ride, saying “OK, I guess we ought to head over to the MEB.” That’s a a replicate of the Main Electronics Box on the Solar Max satellite.

Ron says, “I’ll take you there.”

Bruce jokes, “Just remember one thing, one false move and then blap.”

Ron replies, “Remember one thing, your at the end of the arm.”

Houston gets in on the act, calling, “Challenger, Houston. It sounds like it’s Ron’s turn to get even.”

The MFR activity is a test flight, just like the backpack. McCandless looks like he’s balanced on the end of a pole. Ron maneuvers him to a dummy of the Solar Max electronic box that will be replaced by the next Shuttle flight. Bruce evaluates the motions and forces needed to perform the task. Of the MFR system, he says, “It wobbles a little bit, but it’s a pretty useful platform. You know what I’m doing? — I’m sort of bouncing around intentionally. If you are quiet about what you’re doing, it stays there nicely.”

While this is proceeding, Bob repeats Bruce’s test runs, but his big excursion must be cut due to time to one long run. As he heads out, we tell him, “Be sure and smile some, Bob.”

He checks to see if the unit produces the chatter when the “attitude hold” mode is off. “With attitude hold off, it does not do that.”

We tell him, “OK, you’re [at] 123 ft.”

“OK, Vance, I’ve got good propellant.”

He flies to 150 ft., pauses then continues. Hitting 250 ft. distance, he says, “I see what Bruce was saying about the view out here now that I’ve got some time to look around.”

“Very magnificent.”

He reaches a maximum distance of 305 ft. The radar has no problem locking on him.

Bob returns from his big excursion. And now he attaches the T-PAD for a try at docking with the trunnion pin mounted in the payload bay, and does so successfully, concluding 65 min. flying the backpack. Bruce is still on the end of the arm, working with the mock electronics box. In addition he attempts to fix one of the scientific instruments on the SPAS, the mass spectrometer, by inserting a probe to open a stuck microswitch.

And with that, the main work of the day is done. They stow equipment, close up shop and come back in. As they do, Bruce asks, “What did you think of [our] EVA?” We tell him we liked it all. “It went well.” The spacewalk ends after 5 hr. 55 min. In two days, the pair will have the chance to repeat the experience.

At the end of the long day, Houston tells us, “All of us on the ground want to send our congratulations for a super job today. We certainly enjoyed watching you, and only wished we could have joined you.”

Bruce replies, “Yeah, roger. It was a real thrill, a real honor to be up there.”

Hey — let’s do it again!