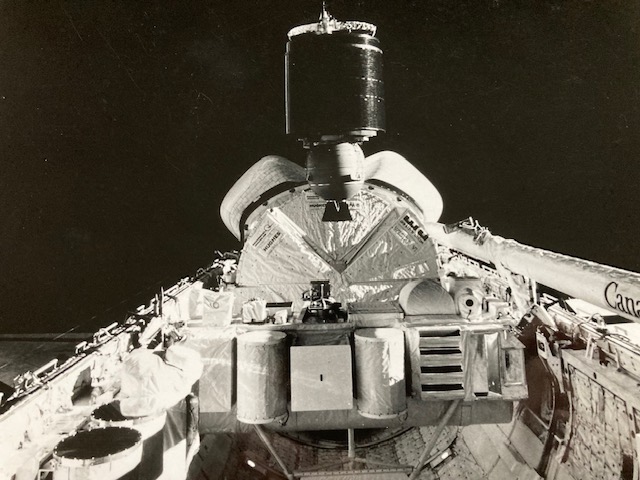

February 3, 1984: The Westar communications satellite rises from Challenger’s payload bay on launch day of the tenth Shuttle flight.

*****

It’s February 3, 1984, and time for us and the workhorse of the Shuttle program, Challenger, to fly. We’re Vance D. Brand, our veteran commander, who first flew in the bygone era of space capsules on Apollo-Soyuz. Beside him, is Pilot Robert “Hoot” Gibson, making his first flight, as the rest of us are: Ron McNair, Mission Specialist, who will operate the Shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS) robot arm, and two people with a special task, Mission Specialists Bruce McCandless and Bob Stewart. They will fly free, unattached to the Shuttle.

Think of us as a flight of firsts, the first tests of the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) jet backpacks — the special province of McCandless, who help develop them, and Stewart. Think of us as a flight of routine Shuttle operations, delivering two communications satellites to orbit. Think of us as a dress rehearsal, as Apollo 10 was to Apollo 11. We’re mapping the moves for the first satellite repair of the Shuttle program.

Think of us as STS – 11. Think of us as the tenth Shuttle flight (because STS-10 which would have used the still-grounded Inertial Upper Stage was canceled). Or think of us as the first crew tagged with a new NASA designation system basically designed to mask changes in the flight order. Our new name is STS – 41B. Confused? Four stands for fiscal year 1984. One stands for a launch from the Kennedy Space Center (flights from California will carry a “two” designation). And “B” stands for the second payload manifested for fiscal 1984. Whatever you call us, in a nutshell here’s our very, very busy mission.

On launch day, we’ll deploy the Westar 6 communications satellite for Western Union. It’s the familiar cylindrical satellite built by Hughes Aircraft that you’ve seen deployed from the Shuttle since STS-5, with a solid-fueled Payload Assist Module (PAM) to boost it to geostationary orbit.

On Flight Day Two, we’ll deploy a second such satellite, Palapa B2 for the island nation of Indonesia. We’ll follow the same script as for Westar.

Flight Day Three will see us assume our role as dress rehearsal for the next flight, STS-13 (now known as 41-C), set for April, will attempt to repair the Solar Maximum Satellite launch in 1980 to study solar flares. Ten months later its attitude control module failed. We will practice rendezvous profile to be used with “Solar Max.” As stand in for the satellite, we carry a silver balloon, with a 6-ft. diameter when inflated, the Integrated Rendezvous Target. We will deploy in from a canister on the wall of the payload bay. Once clear of the bay, it will automatically inflate. We’ll make an engine burn to drift behind the satellite and test our rendezvous radar. On flight day four, after drifting 140 mi. alway, we’ll maneuver for 3 hrs. to approach the balloon from below, finally station keeping with it at a distance of 200 ft.

The real show begins on Flight Day Five when McCandless and Stewart make the first of two spacewalks. Bruce will become the first person to fly the MMU. He’ll be untethered from the Shuttle.. first flying out 150 ft. above the payload bay and back. Then he’ll fly out 300 ft. and back. The two will switch places and Bob will fly the same two profiles.

They’ll also test another piece of hardware for the Solar Max repair, the Manipulator Foot Restraint. It attaches to the end of the robot arm, allowing the RMS to carry an astronaut to various work stations in the payload bay like a utility worker’s “cherry picker.”

They’ll have a rest day — or at least an easier day — on flight day six. We’re carrying the German-built Shuttle Pallet Satellite, SPAS, which flew on STS-7, when it was released for a solo flight and then recaptured. It won’t fly free on our flight, but will act as a stand in for Solar Max on the second spacewalk. And it houses five experiments that Ron McNair will activate.

The second spacewalk will occur on Flight Day Seven. Bruce and Bob will check out a second MMU we’re carrying in runs along the payload bay. They’ll test a docking device that mounts on the front of their spacesuits, called a “T-PAD” (Trunnion Pin Attachment Device). On the next flight, astronaut Pinky Nelson will approach Solar Max in an MMU and dock the T-PAD to a trunnion pin on the satellite. We will practice docking with trunnion pins mounted in the payload bay and on the SPAS. Indeed, Ron will lift the SPAS and set it slowly rotating, as Solar Max will be, and our spacewalkers will practice matching the rotation and docking.

Both EVAs will last about 6 hrs. Flight Day 8 will be devoted to packing up and preparing for our return. The next day, at 7:19 a.m., we hope to make the first Shuttle landing at the Kennedy Space Center.

*

Liftoff is set for 8 a.m., and for once weather is not a worry. Our count proceeds smooth as glass toward an on-time launch. Last steps fall behind us swiftly, Auxiliary Power Unit start, onboard computers take over the last seconds of the launch. Engines swivel into launch position. Feel the stack bend, when the three Main Engines at the Shuttle’s rear fire. Feel the swift, hard, bone-rattling kick as the twin Solid Rockets ignite and we instantaneously leap from the pad. In a blink, we’ve cleared the tower, and Challenger is rolling to the proper heading. Out over the Atlantic we streak on our 8.5 minute ride into orbit, willing ourselves to MECO, Main Engine Cutoff, the first huge step toward placing us in an orbit that is 190 mi. circular.

Vance calls, “We’ve got a MECO.”

“Roger copy MECO.”

“Looks good.”

Welcome to weightlessness. I hope your not prone to motion sickness. We’ll be getting right to work. The twin Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines nudge us into our operational circular orbit. Just 2.5 hrs. after launch, we’ve configured Challenger for orbital operations. We’ve no time to relax — because we’ve gotta start through the long checklists towards Westar deployment set precisely 8 hrs. after launch, 4 p.m. EST. An intense period under Ron’s guidance starts an hour before deploy. We start the satellite rotating on its spin table, as when it is spring-ejected from the bay, it will be spin stabilized like a rifle bullet.

Ron calls, “OK, we’re armed.” Precisely pointing in the correction direction, precisely on time, he deploys the satellite. “Bingo — there it goes.” It gives the Shuttle quite a thump when it leaped out of the sunshield, really got your attention.

Our commander, Vance Brand announces to the world, “Tell all those Westar folks they really have a pretty bird heading out, be heading into geosynchronous orbit pretty soon. We have about 10 eyeballs and five noses all at the window looking.”

About 10 min. later, we make OMS separation burn to put a bit of distance between us, as the Westar will fire the first stage of that PAM — The PKM (Perigee Kick Motor) — 45 min. after deploy. We then turn the Shuttle into “window protection attitude” so that even at a distance the rocket exhaust won’t impinge the windows. And with that our job is done. Westar is now the responsibility of Hughes Aircraft and Western Union. And even they will not have communications coverage of the 85-sec. PAM burn. They should acquire the satellite an hour after deployment.

We begin preparing for our first night in space. And suddenly receive a curious call. Capcom Jerry Ross asks, “Challenger, Houston, for one of the five noses that was pressed against the windows after the PAM deploy, we have some questions for you.”

Bob replies, “Go ahead, Jerry.”

“Roger, Bob. We’d like a little more general information of what you saw as the vehicle went out. Did you see any coning, did you et the chance to see the Omni[antennas] deploy, and were you able to observe the RCS jets activate?”

“. . . When we observed it go out, it looked solid. There was absolutely no coning. We did not observe anything that it — in the way of a jet firing. We could not see the Omni in PAM . . . deploy, and that was, I suppose mainly because we were looking at the wrong end of the vehicle.”

“Roger. Copy and understand that, and understand you did not see any RCS firings.”

“No, Jerry. I did not see anything. It just went out, looked steady as a rock, saw no nutation, saw no activity from it.”

“OK, copy all that. Thank you.”

And everyone goes on to other things.

*

Flight Day 2, Feb. 4

Westar is lost. It’s not where it’s supposed to be. The North American Aerospace Defense Command uses it powerful radars to search, beginning where Westar should be. And it isn’t there. Then they crank in the numbers for partial burns. Nothing at first, then there it is, trailing Challenger, in an odd orbit, 794 mi. by 199 mi.

The impact on our flight is immediate. Today’s Palapa deployment is delayed. Not canceled, but delayed until later in the flight to yield time to determine what went wrong with Westar. If Indonesia doesn’t want to risk deployment, we easily can bring the satellite back with us.

In the meantime our schedule is sliced apart and reformed. We activate the SPAS early, initiate it’s five experiments, move up other experiments and photography tasks.

*

Flight Day 3, Feb. 5

We now have a new flight plan in place. The Palapa deployment is put off until tomorrow. The rendezvous tests are moved up and compressed into one day’s operation. We prepare to eject the canister containing Integrated Rendezvous Target (IRT) balloon. There it goes. A timer is set to inflate the balloon from the canister.

Vance reports, “OK, John, it deployed and it went out real pretty with a very slight toeing angle. It appears to me that it makes about one rotation every 11 or 12 sec.”

“Roger that and what is its current inflation status, Vance?”

“That’s what I’m holding off on it. It doesn’t, it does not look to me like it’s inflated yet.”

“It does not appear that the stays were fired.”

Bundled like a parachute, the stays needed to break to free the fabric of the balloon before it inflated.

Bruce reports, “I’m watching them through . . . binoculars to get a good view. It’s still rotating slowly. It looks like the white thermal cover is still on the top of it. It doesn’t look like there’s been any sort of deployment activity at all.”

Moment later, the balloon tries to inflate.

“Houston, you’re not going to believe this, but it’s just now inflated, and the stays are coming off.”

“Roger, understand, Vance. That’s real good news.”

“We’ll tell you in a minute; we still don’t know if it’s fully inflated.”

“Rog, understand.”

The stays did not come off, and the balloon burst trying to inflate through them. Burst? That’s not the word. Blew up. It demise occurred in a blink, quite violent — pow! — it was in pieces.

“. . . It looks like the balloon blew up. I’m tracking a very large piece of plastic. It stayed white on one side and dark olive drab to black on the other side.”

A bit later, Bruce reports. “We still tracking . . . what appears to me . . . to be the fabric of the balloon. We’re out to 2,200 ft. right now.”

The rendezvous exercise is canceled. However, we can still make important tests of our rendezvous radar, tracking a large piece of the balloon. Bruce tells Houston, “The radar yields a solid lock out to 40,000 ft.” And continues to pick it up intermittently. “Hey . . . as you probably see, we’re locked on again, good and solid with the radar at a range of 51,000 ft. now. It’s been hanging in there for about a minute or so.” The radar’s performance exceeds expectations.

Meanwhile, at 5:30 pm EST, a Hughes tracking station in California picks up a signal from Westar. We’re given the news before we go to bed, “The Westar — they have found the spacecraft and the spacecraft is separated now [from the PAM] and is in an orbit of 155 by 600 mi.”

It’s still alive, in good shape, batteries charging. So it wasn’t the victim of a violent explosion. The nozzle on the PAM must have failed after 10-15 sec. of the burn due to an insulation failure. So now the question: Was it a random, freak failure or result of wider problem with the nozzles? The PAM has made 18 successful flights. It’s Indonesia’s call. And they decide to roll the dice, risk deployment tomorrow.

*

Flight Day 4, Feb. 6

Even though the actual Shuttle deployment has never been a problem on these commercial communications satellite, we feel a bit of tension over this bird. The clam shells of the sunshield open like jaws. The drum-shaped Palapa sits like a tongue in an open mouth. We set it spinning. Out it goes, straight and true, at 10:11 a.m. EST. Looks perfect. But so did Westar.

Bob tells Capcom Jerry Ross, “OK, Jerry, the deploy was absolutely nominal, on time. . .”

“Copy that. Couldn’t ask for any better. Thank you, Bob.”

Yes, we’re anxious, and Bob asks, “Any word from out ex-passenger there?”

“Everything looks good to us so far, Bob.”

We attempt to view the PKM motor burn with a camera on the robot arm. And see it, at least the beginning of the burn. “We saw the beginning of this burn on close-circuit TV, here. . . It sure did [look good] as near as we could tell. It gradually faded out so we never saw the end of the burn but it was rather bright.”

We move on to checking out the EVA suits and equipment for tomorrow’s spacewalk. At 5:30 p.m. EST, Hughes Aircraft releases a statement: “The attempt today to inject the Palapa B-2 spacecraft into a geosynchronous transfer orbit was an apparent failure.” The satellite is stranded in an orbit of approximately 750 mi. by 170 mi.

OK, so things haven’t quite gone as advertized so far, two stranded satellites and a burst balloon. But the meat of the mission is just ahead. If we can pull off these spacewalks, our mission will be redeemed, absolutely. It’s all ahead of us.