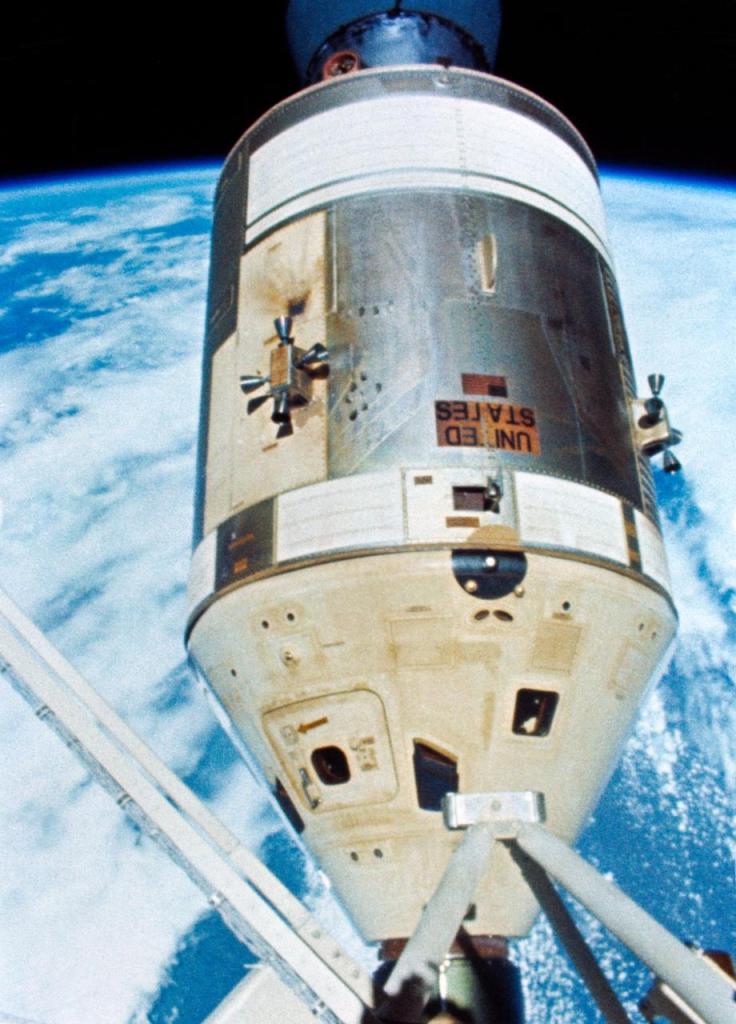

A leaky ship. The Skylab 3 Apollo successfully docked to the space station on July 28, 1973, despite a propellant leak in the thruster system. Two of the thruster “quads” of four engines each are visible on the cylindrical Service Module.

*****

OK, let’s go. We’re going early, our launch originally set for August 17 moved up by 20 days. That’s because the parasol installed by the first Skylab crew (called Skylab 2) is deteriorating fast, weathered by the intense sunlight orbital space. As soon as we can, four days into the flight, we’re going to make a spacewalk and extend a sunshade over it, the twin-pole sail left onboard by the first crew. Just in case that doesn’t work out, we’re carrying an improved parasol. Always have a backup!

We’re also carrying replacements for another system that is in danger of failing, the rate gyros — the small gyroscopes that sense the precise attitude of the space station. One has already failed. We’re carrying a “six pack” of new gyros, strapped into our Apollo ferry ship in two pallets. Packed to the maximum, our Apollo weighs 13,410 lbs, only 90 lbs, under the limit.

We’re the crew of Skylab 3 commanded by Apollo veteran Al Bean, with Owen Garriott riding as science pilot, and Jack Lousma taking the pilot’s position. It’s July 28, 1973, and we’re going. And we’re going to be off planet not for the 56 days originally planned, but in order to align our ground track with the splashdown zone, 59 days, to be precise, 59.5 days.

That’s our ticket to ride, the 22-story-tall Saturn 1B rocket poised like a statue on its pedestal at Pad 39-B. in the predawn darkness vanquished by a bank of spotlights. As we pull up, the white rocket looks like something out of science fiction. Three hours before launch, we enter the conical Command Module.

Everything is going so smoothly. With little to do but wait, Jack actually falls asleep. Then suddenly the last minutes fall away and the Saturn awakens. Al performs the final crew action, a guidance update. T-minus 30 sec. We’re go. Ignition.

And liftoff, we’re underway on time at 7:11 a.m. EDT — or to be precise to the half second, 7:10:50.5 a.m. –rising through some ground fog.

“Roll and pitch program, Houston.”

“Roger, roll and pitch, Skylab. Thrust looks good on all engines,” replies Capcom Dick Truly. The Saturn 1B boasts eight first stage engines.

Al radios, “Got a pretty noise to it right now.”

“Roger, you’re looking good.”

Jack tells Capcom Dick Truly, “Got a great feeling motion up here, Dick, really feel like it’s moving out.”

BECO — booster engine cutoff, just 2.5 min. after launch. A ring of pyrotechnics cut the stage loose with a bang, a shower of debris trampolines by the window.

Jack, wide awake now, says, “We’d like to try that liftoff again. That was great there, Dick.”

Truly, who won’t have a chance to fly for years, replies, “It’s my turn next.”

SECO — second-stage cut-off caps a ride of 9 min. 53 sec. Gravity releases and we’re floating in our straps. We’re on top of the world, feeling wonderful — for now. Eight minutes later, we separate from the spent stage, and move away. We see what appears to be one of our thruster nozzles float by.

Hell –sure looks like a cone-shaped thruster. Na — can’t be. Maybe ice that had congealed inside the thruster, kicked out when it fired. Ice from what? A propellant leak? We have no time to ponder it. We’re flying the normal Skylab rendezvous profile, a series of steps through five orbits over 8 hrs. to bring us to the station.

We make our first burn of our big Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine at 9:26 a.m. It gives a nice kick, and shortly after, see a spray of ice particles blazing in the sunlight. Coming from somewhere on the side of our cylindrical Service Module. A leak.

*

The snowstorm

Coming in range of the Goldstone station, about 45 min. later, we tell Houston, “We got some sort of sparklers going by the right window over by Jack, but we don’t have any going by the left. Maybe we have something spraying out that side.”

Jack says. “It looks like you’re driving through a snowstorm real fast. Some particles look like pieces of frost, others like fine rain.”

Looking at the data, Houston sees a drop in the oxidizer pressure in one of the four “quads” of small maneuvering engines that are placed, 90-degrees apart around the circumference of our Service Module. Each quad houses four engines pointed in four directions, we call them RCS engines, for Reaction Control System. The sixteen engines give precise control for small maneuvers. Each has its own propellant system. The leak is coming from “Quad B” on the port side, and Houston immediately tells us, “Secure Quad bravo,” which means close its propellant valves, shutting it down. That had never been done before during any flight of the Apollo vehicle.

We can maneuver using the 12 remaining engines, but this becomes a complex task to compensated for the dead thrusters. It’s something so out of the box, we’d never even faced it all our simulations of possible failures. The fewer thrusters available, the less “authority” we have during the rendezvous. Yes, authority is the word. And flying this rendezvous puts meat to its meaning. We must step our orbit through multiple thruster and engine burns to arrive at the Skylab orbit at an altitude of 270 mi. We must slide into its orbit precisely at the point pull to a relative stop within 330 ft. of it. Stop too far from it, and we’d have to burn a hell of a lot of fuel to catch up. Fail to slow enough, we could smack right into the side of the 86-ton station.

And now, every time we fire the remaining RCS jets, we have to fire them longer than normal. And our aim must be precise while compensating for the inactive thrusters. Each firing caused the Apollo to yaw a bit — swing to the side — which had to be corrected. All these tasks take our full concentration and teamwork. Rate-range hold the key to the kingdom. That is, measuring our distance from the target and our relative velocity, how fast are we closing in? We don’t the computer systems to calculate rate-range for it. We have to . . . approximate it. Yes, that’s what we do, by taking two radar marks of distance from the target and noting the time we’ve traveled between the marks. Then using a hand calculator, punch in the numbers to provide the answer. So we become human computers, providing data to Al, who is flying the rendezvous.

We first spot the station at a range of 390 mi. We can see four of color-coded flashing docking lights. By their color, we can tell these are on the Apollo Telescope Mount. Closing in, we tell Capcom Dick Truly, “Here’s our home in the sky.”

Our rate-range calculations continue to indicate we’re coming in too fast.

And Al is saying, I’ve put in more braking than I ever did in a simulation.

No, you need more braking, we insist. It’s a tense time of intense concentration, as much as landing on the moon.

The station grows in size, the tower-like ATM slung on top with its windmill solar arrays, the single remaining solar wing on the main body of the workshop, and the golden parasol shield. Now, our science pilot, Owen is excellent as doing the math. So despite some hesitation, Al trusts the numbers. And now he can visually see how fast the approach was. Thanks to Owen’s calculations, we pull to a stop 300 ft. from the massive Skylab complex. We carefully make a fly-around inspection of our new home.

“That parasol is really blowing in the breeze. It looks like a 10 or 15 knot gale every time the thrusters fire.”

Al tell Houston, “We’re drifting away as best we can.”

Houston says, “Do what you think is best to avoid blowing around the shield.”

After 52 min. of playing tag, we move in for a docking at the radial (in-line) port at the end of the Multiple Docking Adapter, the small cylinder protruding under the truss supporting the telescope mount. We dock 8 hr. 21 min. after launch. It’s a smoothy. Coming into communications range, we tell Houston, “OK, we’re docked and that went real well.”.

*

“Stomach awareness”

Our problems are not over. Poor Jack has been feeling motion sick since shortly after reaching orbit, as soon as he began moving about. He’s taken a motion-sickness pill, scopalomine-dextroamphetamine. That does the trick — at least temporarily — and he’s able to lend a hand during the rendezvous.

During the approach, Houston tells us that another rate gyro has failed aboard Skylab. On July 19, the primary “up-down” sensing gyro had failed. As the station is equipped with nine gyros, back ups take over. As the system is vital to keep the station automatically in the correct orientation, we can’t afford to keep losing gyros. The “six-pack” of gyros we’re carrying gives us a healthy margin should more fail. Always have a back up to the back up!

Two hours after docking, we open the hatches and enter the station. The plan has us immediately beginning stowing equipment and activating the station, without a moment to acclimate to our new environment. And we play the price. Jack, who’d managed to truck right along, even eat lunch, becomes sick again. Maybe that lunch did him in. All three of us feel sluggish and nauseous. We have to move very slowly because of what we delicately term to the ground as “stomach awareness.” We ask Houston to be allowed to rest and not move around for a bit. It’s long day — lasting more than 14 hrs. since launch. We hope a night of sleep will revive us.

Mission Day 2 arrives and our hopes are dashed. We’re all feeling it. Al tells Houston, “It’s become obvious to us that we’re just not as spry up here as we’d like to be.” We slog on as best we can. “None of us has been able to eat all our breakfast,” Al tells Houston. “It’s lunch time now, and we are really not too keen on eating much of that either.”

We’re advised to take anti-motion sickness pills, and not to rush our activation activities. We’re also to do perform 10 min. of head motion exercises, the theory being that will help our inner ears adjust. Guess what — tilting our heads vigorously side to side does not improve anything. We’ve got a lot to learn about space motion sickness.

Discussing the spacewalk set for Mission Day 4 to install the twin-pole shield, we tell Houston that we don’t think we’re in shape for it. The walk is delayed by one day.

On Mission Day 3, July 30, we’re awakened early to correct a small air leak through the trash airlock that, manually operated, flushes packed trash into part of what had been the oxygen tank of the Saturn stage. After using the system for the first time, we hadn’t properly positioned the lever to close its hatch.

“Sorry you were so rudely awakened,” says Capcom Bob Crippen, “Hope everybody feels good this morning.”

We ask to be allowed to sleep in in order to recover from the lingering queasiness, and go back to bed for a couple more hours.

We still try the damn head movements. Owen can complete two sessions. Al just one. And our pilot, Jack, can’t even attempt it. We’re pretty damn miserable up here. Our heads feel congested, faces puffy. Without gravity to pull blood to our legs, fluids shift to the head. It will take a few days for the body to relieve itself of what it senses as excess fluid. We’re just learning all this.

On July 31, Mission Day 4, we’re improving but still not quite 100 percent. Still, a day late, we complete most of the station activation and work troubleshooting a malfunctioning condensation tank. We’re working nonstop and Al tells the ground, “If we could just take it easy for a day or so, I think we could completely recover and be ready to go full steam. Everybody worked all day long . . . from the time we got up. We seem to end up with about as many chores to do new as . . . old, so it tends to keep us from really progressing on the activation. It just takes a little bit longer to get going in a used spacecraft, so to speak, then when everything is right in its proper place.”

To help us out, the spacewalk is postponed again, until Mission Day 8, Aug. 4

Finally on Mission Day 5, we’re all feeling much better. Our spirits shoot up. Finally food is beginning to tasting good. Yet we’re kept so busy, now and then we still feel mild discomfort. Al tells Houston, “Say, if you got any friends among the flight planners . . . tell them to give us a little more pass if they possibly can.” He points out we’ve been working since waking “and we’re still not finished . . . and we’re hustling all the time.”

*

Rescue One?

On the morning of Mission Day 6, August 2, as we wake and immediately get to work, telemetry indicates to Houston that temperatures are falling in the Apollo’s RCS Quad D, opposite the failed Quad B. They switch to secondary heaters. Minutes later, Jack, preparing breakfast in the wardroom, looks out the window at shimmering aurora as we passed over New Zealand, curtains of greenish color extending high in the atmosphere. And it notices something else shimmering — a snowstorm of ice particles, the telltale sign of another propellant leak. And we hear the klaxon call of a caution and warning alarm in the Apollo Command Module. Quad D is registering a sharp drop in temperature and pressure. A leak. We close the valves to isolate Quad D. We’re down to two working RCS quads. What if the problem is systemic, perhaps some kind of contamination in the entire system? We might be able to get home on two quads, but dare we trust the system?

Believe me, they’re thinking of that in Houston. Indeed, they’re doing more than thinking. Rescue plans developed long ago are put in play, just in case. Preparation of the Apollo/Saturn for the third mission would become Rescue One. A kit had been devised so that it could hold five astronauts. Lockers under the three existing couches would be removed and replaced with two seats. The Apollo would be launched with two crewmen from the backup crew, Vance Brand and Don Lind, to fetch us home.

A launch, if needed, and that is far from certain, couldn’t happen before September 5. Still, it’s best to keep all options open. Around the clock preparations to launch the Apollo begin immediately.

And what can we do? Since we were safe and secure (unless something goes awry with the station), we’ll carry on with our mission and hope we get the go to stay up a full 59 days.

It’s always good, though, to have a backup.